Why Should I Consider Win Total Futures To Be The Highest Value Bet?

Before I answer this question, I just want to make it clear that gambling, every single type of gambling, is a game of information. What information does the sportsbook have regarding the probability of an event or series of events? What information does the bettor have? Every single time that a person places a bet, they are competing against the sportsbooks in terms of accuracy of probability estimation. It may not seem like it on any individual bet, as it is easier to interpret placing a single bet as competing against people who chose the other side of the bet to see who is right. I will touch more in this idea of a “gambling tax” throughout this page, but in the long run, every bet contributes to a fight versus the “vigorish” (“vig” for short) that is levied against the bettor by the sportsbook. If the average odds of a set of bets is -110 and the amount bet is the same across all of the bets, then as long as the bettor wins around 52.4% of bets, he or she will come out tied against the sportsbook. The only way to attempt a sustainable positive profit is to leverage information against the sportsbook in order to have a higher bet win percentage than the one required to come out even given the average odds of the portfolio of bets.

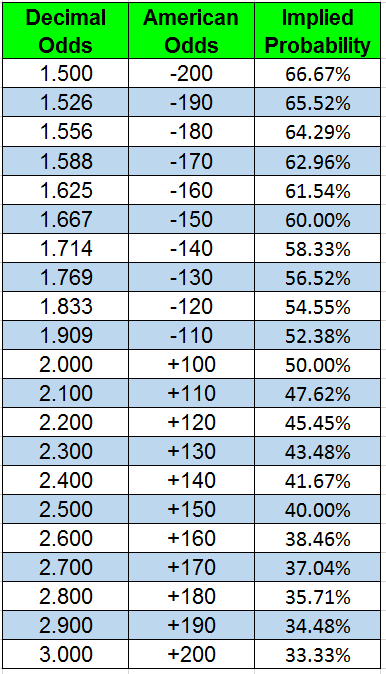

My claim is that betting Win Total Futures consistently produces a higher value than any other style of sports gambling over time. Let’s start off with just the theory itself before going into the evidence. First, let’s assume that every bet you are thinking about taking has the odds of -110, which are the typical odds for betting the Spread or the Total Points. Sportsbooks will typically set bets that they believe to have a 50% probability of winning at -110 odds on both sides. That means that if the bet with a 50% probability is successful, the bettor will receive the original amount of the bet plus 90.91% of the amount bet instead of the additional 100% that one would receive if the bet had +100 odds (which would match the implied 50% probability). Or, in other words, the bettor is losing over 9% of value even when he or she wins the bet. Instead of doubling their money by winning a 50/50 bet (odds of +100), the bettor has to pay a vig, which is essentially a tax, to the sportsbooks. One must pay this tax on every -110 bet that they make. The chart on the right shows this disparity in payout – every 1 unit bet won with -110 odds has a total payout of 1.909 (the Decimal Odds), which is a net win of 0.909 units. The devilish aspect of sports gambling is that if one only takes -110 bets, then on average, he or she will run out of money in the long run, no matter how much money that he or she started with. If one loses -1 unit for every bet that he or she loses and only gains +0.91 units for every win, then winning 50% of bets will create losses in the long run. That’s why a -110 bettor needs to win ~52.4% of bets to come out even. The better the sportsbook is at setting the bets to be a 50/50 chance in terms of probability, the harder it is for a gambler to not lose money, let alone make any money.

You might be thinking, “But that’s just for -110 bets. What if I take bets with steeper odds?” While it’s true that bets with odds greater than -110 will generate more money, they should also be less likely to be successful. From the sportsbooks’ perspective, the difference in probability should cover the increased payout. In fact, it has to in order for it to be worth it for the sportsbooks. If you think about it, if the Moneyline equivalent of a bet (which have odds other than -110) were the better option than the Spread (which typically has -110 odds), then everyone would be Moneyline bettors, and no one would bet the Spread. For example, take the betting options for Super Bowl 58. One could take the Spread of San Francisco 49ers -2 with odds of -110 or the 49ers Moneyline of -128. If that person took the Spread and the 49ers won by more than 2 points, then he or she would receive 190.9% of their bet. But if that person took the Moneyline, and the 49ers won by any amount, then the bettor would receive 178.1% of their bet. This difference in payout is due to the Moneyline being more likely, as it is more likely that the 49ers will win by any amount than win by more than 2 points. In other words, the bettor is willing to give up some potential payout value in order to gain the extra probability of those 2 points. On the other hand, if one bet the Moneyline of Chiefs +108, then he or she would have made more money (208% of their original bet) than the Spread of Chiefs +2, because it is more likely that the Chiefs would lose by less than 2 points than winning by any amount. Knowing what we know now (as I write this in June 2024), the Moneyline bet in favor of the Chiefs with +108 odds would have been the best option. So should you just bet Moneyline? Well here it would have been the right choice, but remember that in the long run, Moneyline should theoretically be the equivalent of the Spread. Odds of +108 have an implied probability of ~48%, meaning that the Chiefs has a 48% chance of winning. If one took bets of +108 odds every time, then he or she should win 48% of their bets in the long run (assuming that the sportsbook is setting the line correctly). While that sounds like a good deal, the numbers do not actually work out in your favor. Winning 208% of the original amount bet 48% of the time is equal to losing 100% of the original amount 52% of the time. Using $10 as the amount bet for the calculation: [($10.8 * 48%) + (-$10 * 52%)] = ~0. In fact, it has to be at least 0 or else the sportsbook would lose money in the long run, and that is not ideal for the sportsbooks as they are for-profit companies. In reality, sportsbooks are likely to set the Moneyline odds so that they gain around the same financial advantage as the vig in Spread bets (+9.09%). Because, once again, if it were not even, then bettors would exclusively using the betting method every time that generated more value for them and less value for the sportsbook.

Instead of using Moneyline or Spread, one could bet via Win Total Futures. Rather than making individual bets, one could bundle them together and avoid paying the vig on every bet. Imagine someone likes to drink soda. One could repeatedly buy individual cans of soda 6 times for $1 per can, bringing the total to $6. Or one could buy 1 6-pack of soda for $5 total, or $0.83 per can. In a similar fashion to the vig, the soda company (or the store) is essentially charging the person for the luxury or flexibility of not having a soda later. By buying the 6-pack, the customer is accepting the responsibility or burden of purchasing 6 cans of soda at that time, even if they just wanted 1 can of soda at the time. In return for accepting that burden, the soda company is willing to charge the customer a lower price. That’s not even mentioning the additional sales tax that one would pay for each of the 6 cans rather than the tax on one purchase of the 6-pack. That’s also not including the idea that the individual can purchases require additional costs, such as the real cost of driving to the store and the opportunity cost of time, when compared to the 1 6-pack. Win Total Futures work in a similar fashion. Let’s use the 2023 Steelers as an example.

Before the season, two people are confident in the belief that the Steelers will win at least half (>9) of their 17 games in the upcoming 2023 season. Using the model in this project, they can see that the ego Win Total Prediction is 9.93, so they agree that the Steelers will win at least 10 games. However, they disagree in how to leverage this information. Person A decides to use Win Total Futures. The sportsbook has set the line at 8.5 Wins and attributed odds of -150 to the Over 8.5 Wins bet. Odds of -150 translates to implied odds of 60%, meaning that the sportsbook believes that there is a 60% chance that the Steelers win 9 or more games. Using this model (given the ego and the line), Person A believes that there is an implied binomial probability of 76% that the Steelers will win 9 or more games. They did end up winning 10 games, meaning that Person A receives 166.7% of his or her original bet amount. Person B, on the other hand, decided to use Moneyline, which would require him or her to make 17 total bets (one bet per week). There are multiple ways to bet Moneyline, and below are three of them.

- Person B could bet a fixed amount that the Steelers win every game. Remember that over time, Moneyline will equal the Spread in terms of value, so one could also bet the Steelers to cover the Spread instead. Although this method is the same amount every bet, the bettor is still risking value each of the 17 weeks against the sportsbook unlike Person A who is competing against the sportsbook a single time.

- Person B could bet different amounts on each Steelers game based on how likely Person B thinks it is that the Steelers will win. By doing so, Person B is going to actively compete against the sportsbook every week. Sportsbooks are extremely good at setting odds and accurately predicting the results of single games, so consistently turning a profit using this method seems incredibly difficult. Sportsbooks are primarily data companies, in that they are able to gather and analyze far more information than any individual person. I have seen a lot of “gambling advice” accounts on social media touting to usage of AI, likely as a potential solution to this problem. However, like with AI in general, I find it hard to believe that they are not grifts.

- Person B could bet only on the specific 10 games that he or she except the Steelers to win. Person B would still be actively competing against the sportsbook every week like in Option 2. However, in this case, Person B is much more likely to miss successful bets and gamble on bets that end up losing. There are many possible combinations, as there are 17 weeks to potentially bet on. In fact, using Pascal’s Triangle, like in the Binomial Probability Explanation page, the total number of combinations is 19448. Regardless, let’s look at some examples using the Steelers actual odds and results using $10 bets:

It’s extremely difficult change the 10-game-bet plan (Method 3) during the season, but let’s say Person B somehow would know the 10 games that they Steelers were most likely to win throughout the season before the season. If Person B bets the Steelers Moneyline on the 10 games that the Steelers were most likely to win (Weeks 14, 13, 10, 18, 4, 12, 1, 2, 15, and 3), then the total result would be -5.09, which could also be described as a loss of -5.09%. If one remembers the idea that in the long run Moneyline and Spread should generate equivalent values, then the result of -5.09% is actually better than the long term average of -9.09%. So Person B has defeated the sportsbook in a battle, but he or she has still lost the war. Let’s say Person B, for some reason, chose to pick the 10 games that the Steelers were the least likely to win (Weeks 5, 11, 17, 7, 16, 8, 3, 15, 1, and 2). The total result would +45, which could also be described as a gain of +45%. The Steelers were very successful as Underdogs (the team not favored to win by the sportsbooks) and poor as Favorites (favored to win), so Person B’s ability to turn a profit by picking 10 games would have been incredibly difficult as the Steelers were extremely unpredictable in their performances.

By comparison, if Person B would have picked Method 1, then he or she would have made a profit of 25.02%. While it is not the absolute maximum profit that Person B could have made, it is the most consistent. Gamblers would have probably been more likely to think that the 7-4 Steelers would have beaten the 2-10 Cardinals in Pittsburgh than the 8-7 Seahawks in Seattle. One might think that I am cherry-picking, intentionally picking the Steelers, but I would recommend looking at any team in the 2023 season and analyze their results, especially with regards to the odds from the sportsbooks. In other words, I believe that it is a fool’s errand to compete against the sportsbook every week. In the short term, the most profitable way to bet Moneyline is to be lucky and somehow choose the correct games to bet on. However, that method will always lead to the bettor missing out on the winners, taking losers, and not being as profitable in the long run.

In order to show proof of the claim above, I decided to use a random number generator to see what the results of a portfolio of random Weeks from above would have been. The table below has the results of 10 randomly generated portfolios. As stated above, 2 of the random portfolios generate a higher ROI (and a larger profit) than any of the portfolios in the table above. However, 2 of them generate a lower ROI (and a larger loss) than any of those above as well. If the number of random portfolios goes to infinity, then the average ROI would approach the ROI of Method 1.

The strongest argument against Win Total Futures is that Moneyline is a less risky bet. When the prediction is wrong, it is much more likely that the Win Total Futures will lose a higher percentage than the Moneyline route. If the Win Total Future loses, it loses -100% of the original amount. But if the majority of Moneyline bets on a team lose, then the rest of the bets on that team, however few, will push the Return on Investment away from -100% and toward 0%. Additionally, the strongest argument for Moneyline in my opinion, which is the higher volume of bets that one can make, is also a double edged sword like Win Total Futures above. If one has a fixed amount of money to put on any single bet (either by decision or due to limitation by the sportsbook) and makes equivalently weighted bets (1 unit) on Win Total Futures and each Moneyline bet, then he or she could bet 17 times the amount that he or she could have with Win Total Futures. Using the Steelers as an example again, Person A put $10 on Win Total Futures and won $6.67, while Person B put $10 on each of the 17 Moneyline bets, winning $42.54. If we did the same for the 2023 Buccaneers, Person A would have lost $10, but the Moneyline bet resulted in -$36.09, an amount much larger than the -$10 from losing the Win Total Futures bet. Overall, as long as we assume that the bettor believes that the ego Win Total prediction will guide them to a success series of bets, either via Win Total Future or Moneyline, then Win Total Futures has a better value (again, in terms of Return on Investment, not necessarily in terms of total amount won by the bettor). No rational bettor would make a bet or commit to a portfolio of bets if he or she thought it would lose. So, as stated and shown above, when things go well in terms of the prediction, Win Total Futures have a higher upside than Moneyline or Spread.

Like with the soda from earlier, Moneyline/Spread gives the customer the flexibility to only buy a can of soda when they want it without being burdened by the additional 5 cans of soda. Win Total Futures forces the customer to buy 6 cans of soda upfront. However, the price difference is what is important. Just like with purchasing soda, the customer will always end up wanting to keep betting, even if they think that they may not. This flexibility will not matter in the long run, as, over the range of one’s life, the presence of a soda currently in one’s hand does not determine the overall frequency of soda drinking by an individual. Whether one buys the single can of soda now or later, it does not necessarily matter to the soda company. Whether one buys 6 cans of soda in a week or a month, flattened over time, the difference is imperceptible over time. Not to say that the soda company does not care about how frequently customers are drinking soda or how many cans of soda they sold in a quarter, but rather, they care more about whether customers are soda drinkers or not. When thinking about the soda company at an existential level, the quarterly results are not necessarily an indication of the long-term viability of the company, but instead, it’s whether or not people generally drink soda or not. In other words, sportsbooks don’t care if one tries to exclusively pick winners or not, because in the long run, they will be continuously betting. With taking the Moneyline approach of picking and choosing which game to bet on, one thinks that they are utilizing the flexibility to just bet on one game a week, but what is one game to a sportsbook if that person is always going to make another bet in the future? If a bettor could live forever, they would make an infinite number of bets no matter whether they bet once a week or once a month. But do not be mistaken, soda companies still do want people to become or remain soda drinkers in the same way that sportsbooks want as many people to become or remain bettors as possible. That’s why sportsbooks compete with each other with account creation deals, because as long as they can lure a person into making an account and betting via their sportsbook, they will make money on every bet made in the long run. Soda companies could do the same buy giving out samples or heavily discounting their soda in order to get people to try their product and become a habitual soda drinker. No matter how a customer buys a soda, either by the can or by the 6-pack, the soda company still makes a profit in the long run, just one way (the 6 individual cans) makes them a little bit more. This project, to finish this analogy, having a long-term positive ROI is like extreme couponing, where not only could I get the customer free soda with a certain set of coupons, but I can theoretically find that customer a deal where the grocery store is essentially paying you in store credit to take the soda that they already purchased from the supplier off their shelves.

What About Bets Other Than Moneyline and Spread?

If I were to continue the beverage analogy, Parlays are like the mix-and-match packs that grocery stores (still?) offer where one pick from an assortment of single bottles of unique, niche beer into a special case. But let’s use soda instead of beer, since that is the beverage that has been used on this page. The customer is paying for the flexibility of picking what he or she wants instead of being stuck with a 6-pack of all the same soda. He or she is paying for opportunity to try new soda, one that could be a new favorite. But in order for it to be a good value, one needs to actually like the soda. Not liking just one soda makes it a worse value than just buying a 6-pack of soda that the customer knows that he or she like and a worse value than grabbing 6 individual bottles of soda that he or she knows that they want (depending on the individual store/deal). It’s pretty well known that Parlays are a horrible betting option. But like in the other sections of this page, let’s put some numbers to that claim.

A Parlay is as if the mix-and-match were $2 for the 6 bottles of various soda. However, at the register, the customer were forced to try a sip of each of the bottles of soda with a lie detector. If he or she didn’t like just one of 6 bottles, then the employee at the register would take out each soda, pour it out in front of the customer, and then not give them their money back. While funny to imagine, it’s pretty much accurate to what happens. Because Parlays are priced odds-wise to be extremely alluring to gamblers, they are often filled with unlikely bets (here, bad tasting sodas), even though the bettor made them (picked the bottles) him or herself. And if just one of those bets fails, the entire thing is worthless. For comparison, another option would be to buy a 6-pack of soda that the customer likes for $5, which can be seen like the Win Total Futures option. Finally, there would be the option to buy 6 individual bottles of the same soda as the 6-pack for $1/bottle (so $6 total), which is like the Moneyline and Spread bets above. Fittingly, the Moneyline/Spread equivalent is a better option than the Parlay in this analogy. For this betting method, if the customer plans on buying 6 individual bottles of the soda over time and cracks open the first bottle, and for some reason it does not taste how the customer thought it would, then he or she could simply not buy the other 5 bottles, saving $5. If the first bet of the potential set/portfolio loses, then the Moneyline/Spread bettor can just stop and not make the rest of the bets, therefore saving the money that could have been lost. In other words, if any bet loses in the Parlay, the bettor would lose the $2, and if a bet loses in the Moneyline or Spread, the bettor could limit their losses to just $1. But the opportunity to get 6 sodas for $2 is too tempting for some people. This phenomenon is perpetuated on social media by gambling accounts like Bleacher Report posting eye-popping Parlay payouts, so that people feel like they could have done the same. It’s extremely effective marketing for the sportsbooks.

But there is an even worse bet than Parlays: Prop Betting. You may have heard about them on the news. One famous example of this style of betting is regarding the color of the Gatorade that gets dumped on the winning team’s Head Coach after the Super Bowl. Prop Bets can be about extremely specific events and events that do not even directly relate to the game. Gambling, not just with sports gambling, is about information. While Prop Bets often have odds that are more favorable, the sportsbooks understand how to scale the odds in order to account for the change in probability. Depending on those odds, the percent of bets required to win in order to come out even could potentially be lower. But there is no way to have information about what the color of Gatorade will be. Sure, probably no one else betting on that knows either, but every time the person bets against the sportsbook, he or she is risking a loss. With this frame of reference, Prop Bets are extremely careless. Very little information is available to, and being used by, the bettors for these wagers.

If I were to equate the Prop Bet to the soda analogy above, it would be like if the grocery store sold opaque cans of soda with no label on them. The deal would be that the customer can pay $0.25 for the can if he or she can guess what the soda is in the can before opening it. If the customer is incorrect, then the can gets taken away, and the customer does not get his or her money back. Even if the store caps the number of possible sodas at just 5 with a 20% chance of it being any of the 5, the deal is not worth it. In the long run, for every 5 attempts, only one will be successful, meaning that the customer would be paying $1.25 for a can of soda that he or she did not intentionally chose instead of a soda that he or she would want at $1. The entry price that would make the deal worth it for the customer would be $0.20. Anything less that that price would be advantageous for the customer and not worth it for the grocery store. At a price of $0.25, the customer is losing $0.05 of value on every attempt, or in other words, the customer is losing 5% of value on each attempt. This loss of value on each attempt is synonymous with the vig in gambling, except the vig in gambling is almost always 9.09% (sometimes you will see odds of -115/-115 which would be a vig of ~13%), much larger than that 5%. Instead of charging $0.25 per attempt, imagine if the grocery store were charging around $0.29 per attempt. That is basically how sportsbooks operate to consistently make a profit. Not just with Prop Betting, but with sports gambling in general. However, the situation is more complicated and nefarious in sports betting when compared to the soda example. The probabilities are not obvious; the sportsbook simply puts out lines and odds. And instead of using an easy-to-understand price like a grocery store, the sportsbooks use lines and odds, adjusting the “price” to match its calculated probability. So it is extremely difficult for people to tell that they are overpaying compared to the “fair” value ($0.20 in the soda example), especially over time. Just like with the soda deal, it may be fun for a bettor to see if he or she is lucky one time, but the Prop Betting style of gambling is certainly not sustainable.